October marks Cyber Awareness Month, which usually brings an emphasis on phishing campaigns, password policies, and practical tips for staying safe online. These reminders have their place, but they only touch the surface of what awareness should mean. A more fundamental issue, in my view, is how we maintain human agency in a world where artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly embedding itself across cyber operations.

AI is now part of most areas of cyber defence. Machine learning models classify events and correlate alerts, large language models summarise threat intelligence, and automated response engines prioritise actions or recommend controls. These tools are extending the reach of defenders and raising overall efficiency. Yet they also alter how decisions are made and by whom, and this shift in decision control is reshaping the balance of human and machine agency in ways that deserve a closer look.

One of the best pieces I have read on this broader topic of agency is George Mack’s High Agency in 30 Minutes. He defines high agency as the ability to act decisively and creatively despite constraints, and to view problems as things to be solved rather than reasons for inaction. I find that framing particularly relevant to cybersecurity, where the conditions are rarely stable, information is often incomplete, and progress depends on the willingness to act under uncertainty.

Where are we gaining and losing agency in cyber defence?

AI is increasingly playing an essential role in cyber defence, yet every layer of automation carries both benefit and trade-off. The benefit lies in speed, scale, and consistency. The trade-off lies in the gradual displacement of human interpretation. As more decisions are pre-defined by models, defenders risk relying on outputs that they no longer fully understand. The question is not whether automation is valuable — it clearly is — but whether it remains an extension of human intent or becomes a substitute for it.

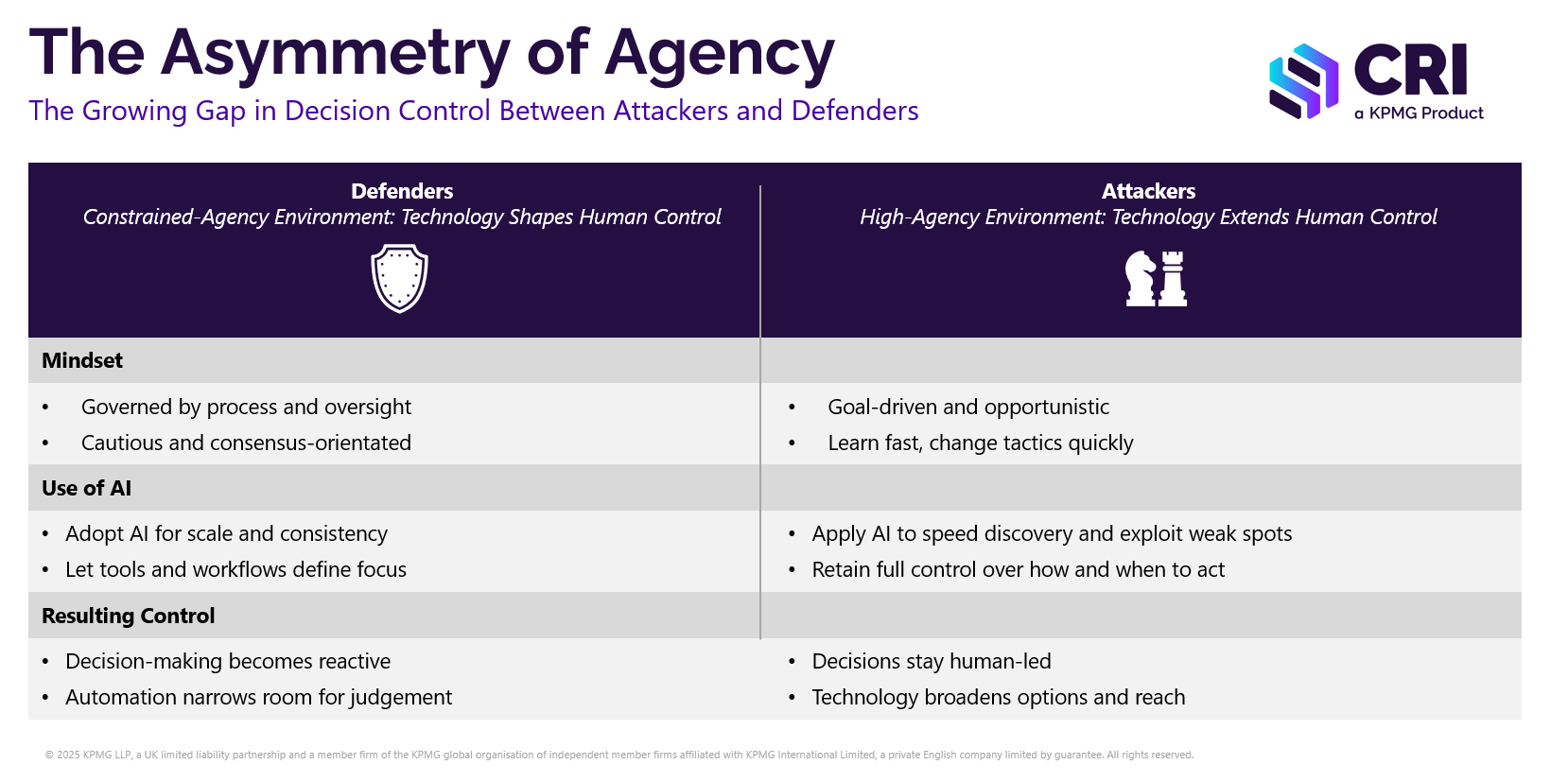

Attackers have already shown how powerful technology can be when human purpose stays firmly in charge. They use AI to accelerate reconnaissance, tailor social-engineering campaigns, and develop adaptive malware that learns from each attempt, yet their decisions remain entirely human-driven.

Defenders, on the other hand, operate within environments built for control and accountability. Decisions are shaped by governance, regulation, and the need to coordinate across many teams. Those safeguards are essential, but they also slow adaptation and make it harder to act on judgement when speed or experimentation is needed.

Over time, this creates an asymmetry of agency — attackers use automation to extend their control, while defenders risk allowing automation to constrain theirs. That imbalance will likely only grow as AI systems become increasingly capable. The answer is not to resist AI, but to design consciously for human control within it, ensuring that efficiency never comes at the cost of understanding or accountability.

How can high-agency thinking strengthen cyber decision-making?

Mack’s ideas about clear thinking, bias to action, and constructive disagreeability translate well to cyber risk.

Clear thinking demands precision about what is known, what is estimated, and what remains uncertain. Bias to action means moving forward when information is sufficient, rather than waiting for it to be perfect. Constructive disagreeability means creating room to challenge consensus, especially when that consensus is shaped by tools or reporting conventions that may no longer serve their purpose.

Mack also highlights the traps that reduce agency: conformity, overthinking, and answering the wrong question. These show up often in cybersecurity. Teams spend months designing metrics frameworks or maturity models that appear rigorous but do little to change outcomes. The difference between high- and low-agency teams is rarely about technical skill; it is about how they approach decisions and challenge the status quo.

One practical expression of this mindset is structured judgement — the ability to combine data, context, and expert insight in a transparent way. In many organisations, quantitative data is partial or uneven, and qualitative insight fills the gaps. Structured judgement makes that reasoning defensible. It keeps uncertainty explicit rather than concealing it behind assumptions or scores, and it creates a shared language between technical teams and senior decision-makers.

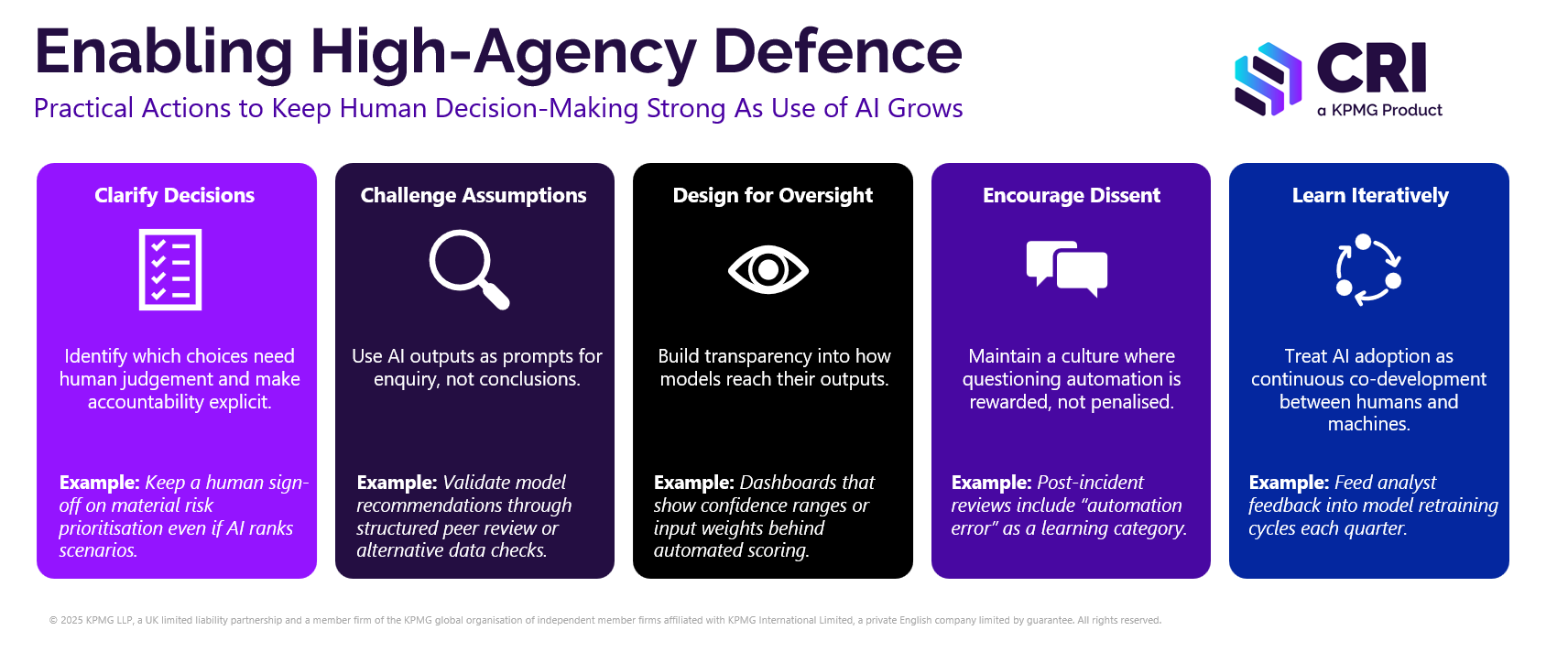

In our work with CRI, we believe in using AI in precisely this way: to surface the right data and insight in front of the right person at the right time, enabling more transparent, evidence-based judgement. This, to me, is where the potential of AI in cyber risk truly sits — not in replacing human decision-making but in strengthening it.

How do we sustain human agency as AI scales?

As AI becomes embedded in more layers of cyber defence, the real risk is not automation itself but the gradual erosion of ownership. When tools analyse, prioritise, and recommend at scale, it becomes easy for people to mistake visibility for control. Sustaining agency means being clear who owns each decision, how confidence is assessed, and when human reasoning should override model outputs.

In high-agency organisations, automation accelerates execution but never replaces challenge and reflection. Teams still take responsibility for the logic that drives recommendations, and they keep questioning whether the model still reflects reality. Over time, that discipline preserves both transparency and trust - two qualities that are hard to rebuild once they are lost.

George Mack makes the point that low agency is our default setting. We are built for efficiency and conformity, not for questioning the system we inherit. Yet, as he says, we have agency over our agency. I think that is a fitting reflection for cyber risk too. Even in regulated or process-heavy environments, we can still choose to make decisions in a more high-agency way: by clarifying assumptions, testing what the data really shows, and acting with intent rather than compliance.

Human agency is how strategy, ethics, and accountability are expressed in practice. Sustaining it will remain one of the defining tests of effective cyber defence.